Has anyone ever pointed out a new glassy high rise, or a gutted out old building in Chicago to you and said something like “Oh yeah, ‘they’ are putting new condos here.” I think the 2000s condo boom etched the idea into people’s heads that large scale development must equal homeownership. In reality, next to none of these high profile developments you’ve seen popping up over the city in the last decade have been condos. Why would developers throw so much weight behind rental housing in a country where 66% of the population are homeowners?

The reason so many of the condos in these areas look how they did both internally and externally when they were originally built as apartments over 100 years ago is economic over aesthetic. Small landlords wanted to have to do as little work as possible to maximize their profits. After the building goes condo and after the articles of incorporation are issued and the control is shifted from the landlord to the HOA, changing a unit’s layout and moving common plumbing and electric around to accommodate a single unit’s needs is extremely difficult to orchestrate. This level of construction in one unit depends on the cooperation of the entire HOA who all have a shared interest in the building’s utilities.

It didn’t take long for investors to notice this trend. Nor did it take them long to notice to continued trend of young professional migration to Chicago’s city center without new product to meet the demand. In the years prior to 2008 rental units added annually in Chicago rarely surpassed several hundred units. By the time the mid 2010s rolled around Chicago was adding over 3000 rental units annually.

It wasn’t just large scale institutional money noticing this trend of rent prices increasing amidst diminished buying power. Small scale landlords were getting into the market too. 2-4 Unit prices in Chicago have jumped 260% since 1/2014 with a 26% jump between 2020-2022 alone. Low interest rates and the trend of “house hacking” online content fueled this boom in many first time home buyers locally opting to buy multi unit buildings over condos.

In the midst of the last condo boom, for every glassy, luxury amenity filled high rise unit, there existed an affordable counterpart in an old retrofitted Chicago apartment building. While first time buyer demand for these downtown units have been stifled by high HOAs, transient attractions to downtown and diminished cultural relevancy, the existing condo market in the neighborhood turn of the century walkups is still soaring. So why aren’t we building more of them?

The idea of protracted home ownership timelines fueled by data on millennial and Gen Z household wealth vs Gen X and Boomers at the same ages still keeps builders’ confidences in Multi Family projects over condo conversions for mid priced existing buildings. Higher rent prices in these buildings means higher property valuations which make buying an expensive multi family building untenable for a profitable condo sell out when factoring in the construction costs to bring units to market.

Condo conversions are not what they once were. Even if building codes hadn’t changed since the 70s, buyers are just too savvy now to buy into an old apartment building where the mechanicals, windows, roof, brick haven’t been touched by the developer as was the former practice. The standardization of home inspections in transactions, more rigorous building codes and insurance standards have made these simple conversions to condo from beat up vintage buildings all but impossible today.

Developers these days are most confident in the luxury market for large condos that can act as single family home alternatives in tried and true upper middle class neighborhoods. With enormous price growth and demand for single family homes at an all time high in these neighborhoods, a sub market for larger scale condos has emerged.

The thought behind this is even at historically high prices these 3-4 bedroom multi level condos are still priced at market between 40-60% of the cost of a single family home with a comparable level of finishes in the same areas. With no end in site to the boom in SFH prices, this allows buyers to experience the conveniences of these inner ring neighborhoods and have a large enough space to satisfy multiple living arrangements.

Looking at this concept in practice:

This lovely house in Lincoln Park seemed to be totally suitable for single family occupancy but because of the prime location and wider than average lot it was torn down 16 months ago and replaced with 3 condos. Sold for $1.3m.

The Condos:

The sale price for each condo was:

Top Floor: $1.385m

Middle Floor: $1.099m

First Floor(duplex down) Under Contract with asking of $1.649m

Even if this seems high in price to you. Keep in mind the median sale price of a 4bed house in Lincoln Park is $2.1m. This trend has continued to grow, especially in the dozen or so North Side neighborhoods with high density and exceptional school districts.

What has shaped up to be one of Chicago’s most shameful legacies was a policy called Urban Renewal. Through the use of several new state and federal postwar laws both with some ease the city was able to use eminent domain to tear down unfathomable amounts of Chicago’s early pre war housing stock, displacing thousands and destroying entire neighborhoods. Chicago hit its peak population of 3.6 million people in the late 1950s and anxieties of housing shortages, plus a growing suburban middle class exodus threatened to put the city’s tax base (which was then far more dependent on the residential neighborhoods) at risk.

Real concerns on public health, coupled with well entrenched neighborhood racism fostered many of these ideas. Much of the remaining housing in neighborhoods in and around Bronzeville, North Kenwood, Oakland, Douglas, Woodlawn that we cherish today like the beautiful stone mansions of the 1880s up and down the boulevards were often converted to rooming houses to support a massive influx of migration post WWII. These buildings were woefully overcrowded and many did not even have indoor plumbing. Most of the residents of these buildings were black and many had recently arrived from other parts of the country.

The Kennelly and then later the first Daley administration’s strategy towards modernization and potentially stemming the tide on suburban outmigration was to use the powers of the Chicago Land Clearance Commission to tear down enormous swaths of land and to build vertically. Community support for land clearing policies in parts of the city was often easy to find due to fears of the “black belt” expanding into surrounding middle class neighborhoods. Whole neighborhoods were destroyed and in their place came massive concrete towers with huge setbacks surrounded by open land: The infamous public housing complexes of Chicago.

City planners for these areas rarely factored community input into their decisions for best land use protocols. Whether explicitly spoken of or not, urban planning concepts from Europe and the Soviet Union were often favored: Demolish low rise housing stock and replace with nondescript mid and high rise buildings set back on large land parcels.

Of course, many displaced residents were unable to move into these new buildings and those who did were packed into overcrowded, austere structures. The surrounding open land was always underutilized and often became hotbeds for the exploding crime rates of the 70s-90s.

32nd and Rhodes in the early 1940s (top) vs. 32nd and Rhodes now (bottom).

The Kennelly and then later the first Daley administration’s strategy towards modernization and potentially stemming the tide on suburban outmigration was to use the powers of the Chicago Land Clearance Commission to tear down enormous swaths of land and to build vertically. Community support for land clearing policies in parts of the city was often easy to find due to fears of the “black belt” expanding into surrounding middle class neighborhoods. Whole neighborhoods were destroyed and in their place came massive concrete towers with huge setbacks surrounded by open land: The infamous public housing complexes of Chicago.

City planners for these areas rarely factored community input into their decisions for best land use protocols. Whether explicitly spoken of or not, urban planning concepts from Europe and the Soviet Union were often favored: Demolish low rise housing stock and replace with nondescript mid and high rise buildings set back on large land parcels.

Of course, many displaced residents were unable to move into these new buildings and those who did were packed into overcrowded, austere structures. The surrounding open land was always underutilized and often became hotbeds for the exploding crime rates of the 70s-90s.

The population boom previous administrations predicted never came and these large scale public housing complexes were torn down leaving mass swaths of open land. By 2000, Chicago’s population had not grown to the 5 million residents that planners in the late 50s had predicted. In fact, the current population is 800,000 less than when these policies were enacted. Net population loss over the last 70 years greatly exacerbated disinvestment leading to more depopulation, more abandonment, and more teardowns.

Today, we still have 30,000 vacant parcels of land in Chicago. 10,000 of these are city owned. How is this possible in a city with a world class economy and in a nation with a massive housing shortage and affordability crisis?

Infrastructure:

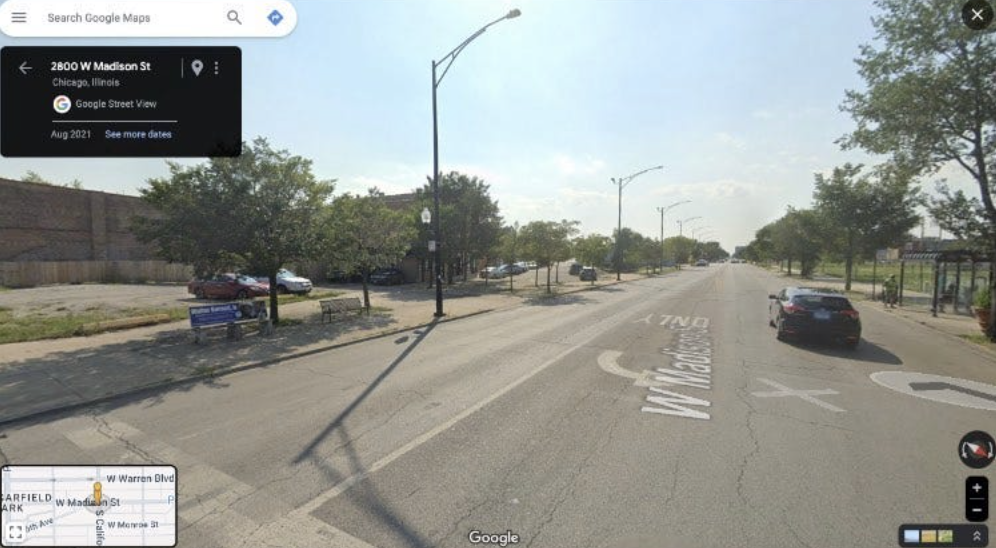

While many of the neighborhoods most affected by Urban Renewal land clearance are still rich with transit options, the walkability and livability indexes in these areas remain woefully low due to mass commercial tenant loss on their main corridors.

Once booming intersections and commercial corridors have been either long boarded up or reduced to rubble over the years. If not directly from Urban Renewal initiatives, depopulation lead to reduced customer base, which ultimately lead to vacancy, abandonment and then demolition.

With an already reduced demand for brick and mortar retail and office space, getting financing to build mixed use or solely commercial buildings in low income, low density neighborhoods has proven next to impossible. Federal initiatives like Opportunity Zones have bore little fruit so far in Chicago and local programs to build affordable housing developments are coming in with shockingly high construction budgets. Major big ticket affordable housing projects in Chicago are far exceeding the market rate for similar size units, sometimes even exceeding the cost of ultra luxury units of the same square footage.

Madison, California, and 5th in the mid-1950s (top) vs. Madison/California and 5th now (bottom).

Construction Costs:

It’s no secret that construction costs both on labor and material have skyrocketed over the last four years. Overall cost of residential construction is 38% higher now than in February 2020. In addition, interest rates have more than doubled with many construction loan products topping 10% interest carry. While housing prices have gone up substantially as well, the margin between build and sale price has slimmed leaving builders with less profit.

When profit margin shrinks to these levels, far fewer developers are willing to take big risks on areas without a tried and true history of sales that will assure them that their target exit price is attainable. Lack of risk and unreliable demand in areas with high vacancy is one of the major reasons why you’re seeing seemingly nonsensical teardowns replaced with higher density condos in our wealthiest neighborhoods.

Zoning:

One of the biggest ways developers have been looking to maximize profit amidst rising construction costs has been through adding density to projects. Higher density and unit count is a win-win for both the builder and the purchaser. Stacking the parcel with condos often yields a higher return for the builder and affords the buyer an opportunity to buy in an area where a single family home may be out of their budget.

The problem with this is Chicago’s most common zoning code, RS3 and its Lot Area Per Unit do not allow for the construction of anything other than a single family home. In areas where developers are taking a bigger risk, not being able to hedge by packing the lot with a higher unit count is a bridge too far. What’s worse is this zoning code post dates the majority of buildings in Chicago. Huge turn of the century or 1920s buildings are often non compliant with the 1957 zoning code foisted on them. This means if a building is in bad enough shape to require a teardown, a new building in its place could only be a single family home without a zoning variance.

When profit margin shrinks to these levels, far fewer developers are willing to take big risks on areas without a tried and true history of sales that will assure them that their target exit price is attainable. Lack of risk and unreliable demand in areas with high vacancy is one of the major reasons why you’re seeing seemingly nonsensical teardowns replaced with higher density condos in our wealthiest neighborhoods.

Parking:

The problem with this is Chicago’s most common zoning code, RS3 and its Lot Area Per Unit do not allow for the construction of anything other than a single family home. In areas where developers are taking a bigger risk, not being able to hedge by packing the lot with a higher unit count is a bridge too far. What’s worse is this zoning code post dates the majority of buildings in Chicago. Huge turn of the century or 1920s buildings are often non compliant with the 1957 zoning code foisted on them. This means if a building is in bad enough shape to require a teardown, a new building in its place could only be a single family home without a zoning variance.

When profit margin shrinks to these levels, far fewer developers are willing to take big risks on areas without a tried and true history of sales that will assure them that their target exit price is attainable. Lack of risk and unreliable demand in areas with high vacancy is one of the major reasons why you’re seeing seemingly nonsensical teardowns replaced with higher density condos in our wealthiest neighborhoods.

Appraisal Issues:

One of the most glaring issues preventing market rate for sale housing stock from being built in neighborhoods rife with inexpensive plentiful vacant lots is the prospect of the buyer being able to find financing.

With construction prices at an all time high, being the canary in the coal mine building or buying in a neighborhood without sufficient sales comps is going to have you wringing your hands praying for the unit to appraise at contract price. If the unit doesn’t appraise out at value the buyers are then forced to either change their loan to value ratio or put up more cash to close.

Some of these areas have never seen a condo development even in the early 2000s boom times. Appraisers are not infallible and banking on them sharing the vision the builder and buyer have for an area with no prior similar sales is just too big a risk for many.

When profit margin shrinks to these levels, far fewer developers are willing to take big risks on areas without a tried and true history of sales that will assure them that their target exit price is attainable. Lack of risk and unreliable demand in areas with high vacancy is one of the major reasons why you’re seeing seemingly nonsensical teardowns replaced with higher density condos in our wealthiest neighborhoods.

Charlie Cohen is a Senior Broker and Sales Leader at Cross Street.

Throughout 10 years in Real Estate and as a Senior Broker at Cross Street, Charlie has closed hundreds of deals from apartment leases to sales of multimillion dollar homes and apartment buildings, cafes, industrial space and everything in between. Charlie uses his network and background in investment property acquisition, management and construction to apply an analytical approach to home buying, from helping clients understand the importance of different period aesthetics and build quality to financial analysis and specifically tailored borrowing options.

Join our mailing list to receive notifications every time a new blog post is live.